Easy to learn, hard to use

Apps so simple you can't get anything serious done

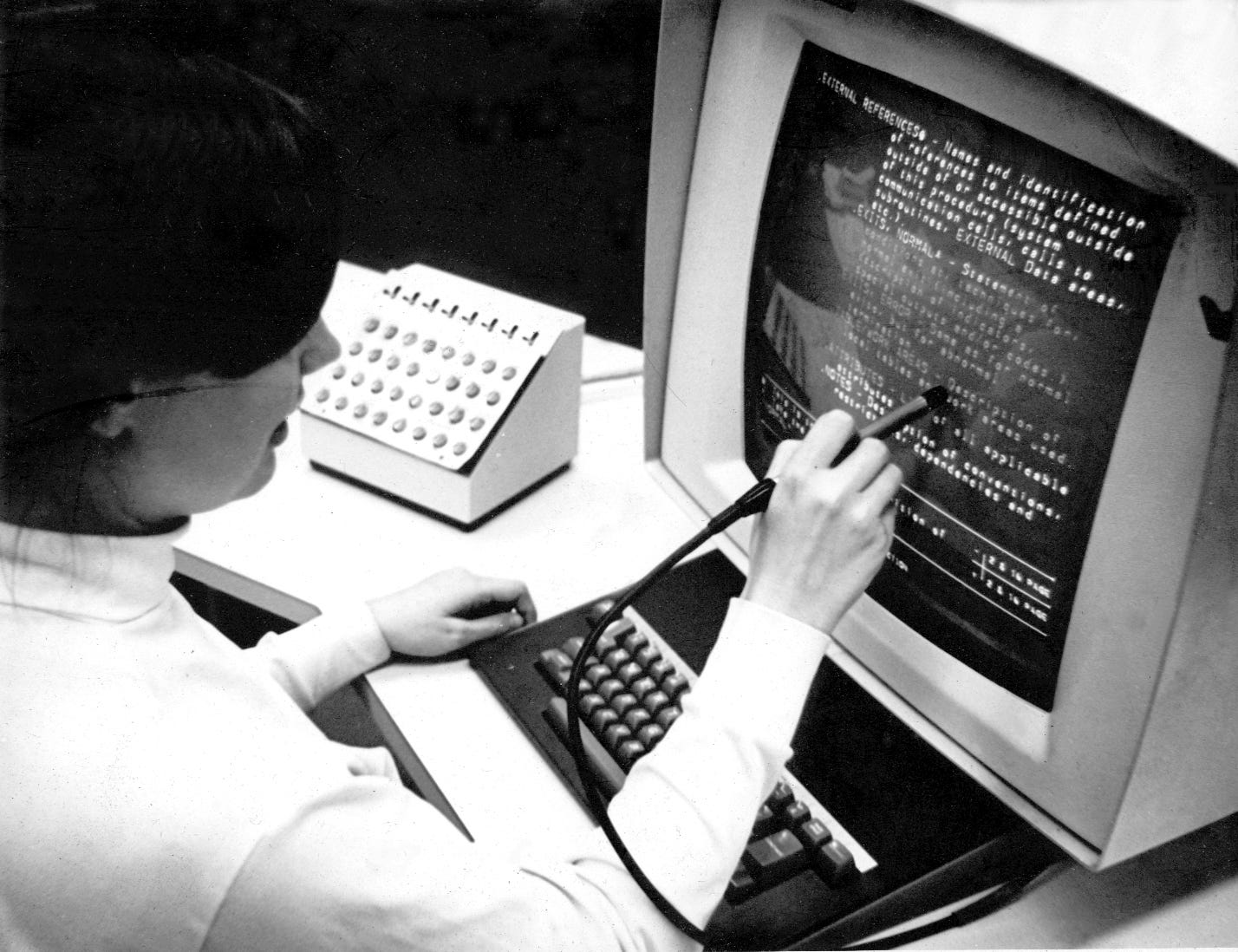

We live in a world of light pens

I keep coming back to this video from Mike Caulfield, where he describes the concept of “hard to learn, easy to use” in a way that feels relevant to Continuous Onboarding, so I thought I’d share my thoughts.

Before Douglas Englebart invented the computer mouse, we had the light pen. You can think of it sort of like a stylus people would use on their computer screens. People were already familiar with how to use pens on paper, so within 5-10 seconds, people could figure out how to use it. The mouse was trickier. It had multiple buttons, and moving a cursor around on the screen by moving your hands on a table was a weird notion for the time. A mouse afforded more possibility and comfort, but it had a learning curve.

When Doug would put two people against each other on the same task, mouse users were initially slower, but "very quickly they start[ed] to outpace the person with the light pen, and they start[ed] to achieve a fluidity of speed and expertise that the person with the light pen never achieves."

We live in a world of light pens. We infantilize people with software that is built to be intuitive from the start but can't do anything serious because the developers were scared of requiring the user to learn anything new.

From the video:

"People are bragging that infants can use iPads as if this was a point of pride rather than something horrifying… This is why we live in a world where most things are easy to learn, but hard to use. By hard to use, I don't mean that we feel they are difficult, but that we never reach our capacity to meld with these systems because we've chosen this path."

The user’s journey to expertise

Don't get me wrong, upfront onboarding can be a perilous time. Without the right kind of supportive design, you lose users. Many apps are both hard to learn and use, and I would bet they have high churn. But we don't need to be afraid - we just need a better framework for understanding the user's overall learning journey. This is what I'm trying to communicate through Continuous Onboarding.

We don't need to teach the user everything at the beginning. We can spread learning out as long as users recognize that their own involvement is bringing them closer to goal accomplishment. That is what motivates them to keep at it. As designers, we need to think of user involvement as a resource we get to tactically spend, while recognizing our tools to increase user involvement through motivational techniques.

I'm a big believer in "low floor, high ceiling." It shouldn't take much effort or time to gain value out of the system. As the user's skill grows, user goals will get more sophisticated and varied. If we want to retain users, we need to cater to their six month goals just as well as their first week goals.

“North star for Roam Research is Excel. Easy enough for 750M people to use, powerful enough that you can spend your whole career working 40+hr a week in it and still find new ways to use it. Low floor, High Ceiling - to quote Gordon Brander”

“Intuitive design" should be less about designing an app with immediately obvious interactions and more about design that builds intuition through feedback loops. This distinction is especially important if you're building an innovative product, where users lack prior intuition.

I wish app developers and designers would think seriously about creating a smooth learning curve from novice to expert. What are the stages of development, and how do we facilitate the ramp up? How are users likely to fail along the way, and how might we help them recover? Continuous onboarding! I don't get why everyone expects all onboarding to be upfront. We should instead focus on the behavioral science of building expert intuition and facilitating goal accomplishment for inspiration.

The question we need to ask is: how might we make it rewarding to progress along the path to power user?

Preview

In my next newsletter, I’ll either be talking about:

Clippy. It’s such a juicy historical Continuous Onboarding example, I have to write about it. It’s instructive in the ways that it failed, and modern LLM technology might make its better ideas possible. Many of Clippy’s fundamental design considerations are still valid.

My experiments using Langchain and GPT to support my writing process.

Designing for failure states. This is one of the most important parts of my strategy for retention. When your user inevitably fails, how do you decrease the likelihood that they give up, and increase the likelihood of forward progress?